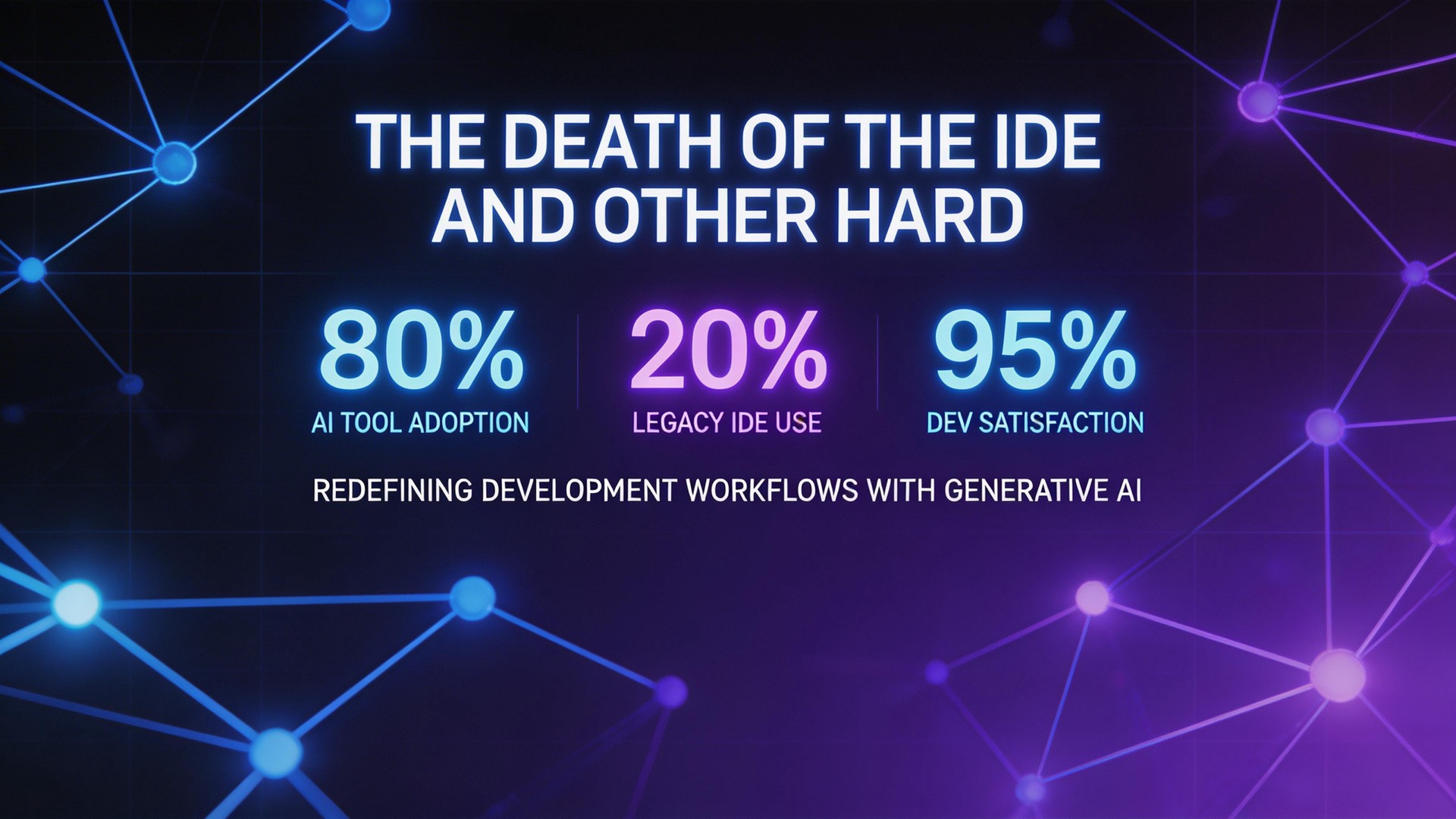

The Death of the IDE and Other Hard-Won Lessons from a Year of Agent Programming

David Crawshaw has been on the front lines of agent development since before Claude Code launched. His latest update after eight more months reveals surprising conclusions—including why he’s abandoned his IDE for Vi.

The Core Insight

A year ago, agents could help with some things, some of the time. Today, Crawshaw reports a staggering shift:

“In February last year, Claude Code could write a quarter of my code. In February this year, the latest Opus model can write nine tenths of my code.”

His time allocation has transformed accordingly. At big companies, he used to spend 80% reading code, 20% writing. At startups, 50-50. Now? 95% reading, 5% writing.

The code still needs careful review and regular adjustment—but the model handles the adjustments too.

The IDE Reversal

This might be the most surprising take: Crawshaw no longer uses an IDE.

Consider the history: In 2021, Copilot made IDEs seem inevitable. LLM-assisted auto-complete was too powerful to ignore—50% more typing efficiency on typing-limited tasks. The IDE had won.

Four years later? He’s back on Vi.

“The degree of certainty I felt about a copilot future, and the astonishing whiplash as agents gave me a better tool not four years later still surprises me.”

The only IDE feature he still uses: go-to-def, which neovim handles fine.

Vi is turning 50 this year. And it’s somehow the tool of the future.

Hard-Won Lessons

1. Frontier Models or Nothing

Crawshaw is blunt about model selection:

“Using anything other than the frontier models is actively harmful… you do worse than waste your time, you learn the wrong lessons.”

The reasoning: working with agents means constantly discovering limits. Those limits keep moving. If you’re using a cheap model like Sonnet or a local model, you’re learning the wrong limits—and optimizing for constraints that won’t exist when you upgrade.

Local models will eventually catch up. But until then, “pay through the nose for Opus or GPT-7.9-xhigh-with-cheese.”

2. Built-in Sandboxes Are Broken

The constant permission prompts from Claude Code (“may I run cat foo.txt?”) and sandbox failures from Codex are productivity killers. The solution:

“You have to turn off the sandbox, which means you have to provide your own sandbox. I have tried just about everything and I highly recommend: use a fresh VM.”

This is what Crawshaw is building with exe.dev—a VM with an unconstrained agent that can trivially spin up and execute one-liner ideas that would otherwise rot in a TODO note.

3. More Programs Than Ever

The shift isn’t just about coding faster. It’s about having code that exists at all:

“A good portion of the time Shelley turns a one-liner into a useful program. I am having more fun programming than I ever have, because so many more of the programs I wish I could find the time to write actually exist.”

This is the productivity unlock that’s hard to measure: the software that never got written because there wasn’t time, now gets built.

4. Software Shape Is Wrong

Most software was designed for direct human interaction. That assumption is increasingly obsolete.

Crawshaw’s example: Stripe Sigma, a SQL query system with an integrated LLM helper. Nice idea—but the LLM isn’t very good, and the API for programmatic access is still in private alpha.

His solution? Three sentences to his agent:

1. Query everything about his Stripe account via standard APIs

2. Build a local SQLite database

3. Query against that instead

“I implemented that entire Stripe product (as it relates to me) by typing three sentences. It solves my problem better than their product.”

This pattern will repeat everywhere. Products built for human UIs will lose to raw APIs that agents can consume directly.

5. A New Philosophy

Crawshaw’s emerging principle:

“The best software for an agent is whatever is best for a programmer… Every customer has an agent that will write code against your product for them. Build what programmers love and everyone will follow.”

Product managers have long told engineers “you are not the customer.” That’s being inverted. When every user has an AI that codes on their behalf, the programmer experience is the user experience.

The Anti-LLM Disconnect

Crawshaw acknowledges legitimate concerns about labor market disruption and real pain from technological change. But he finds himself unable to engage with harder anti-LLM takes:

“It sounds like someone saying power tools should be outlawed in carpentry. I deeply appreciate hand-tool carpentry and mastery of the art, but people need houses and framing teams should obviously have skillsaws.”

The statement seems obvious to him now—as obvious as “water is wet.”

Key Takeaways

- Agent harnesses haven’t improved much; models have improved dramatically — The gains come from better models, not better scaffolding

- The IDE era was shorter than anyone expected — Four years from Copilot victory to agent replacement

- Use frontier models even when it hurts — Learning the wrong limits is worse than paying more

- Fresh VMs beat built-in sandboxes — Agent-native infrastructure is a gap waiting to be filled

- Software needs reshaping — Products designed for human UIs will lose to API-first designs that agents can consume

Looking Ahead

“Most software is the wrong shape now. Most of the ways we try to solve problems are the wrong shape.”

The next year of LLM-driven change will require rethinking assumptions that seemed solid just months ago. The philosophy that might survive: build what programmers love, because everyone now has a programmer working for them.

Hopefully that philosophy survives the next year of changes too.

Based on analysis of “Eight more months of agents” by David Crawshaw

Tags: AI Agent, Developer Tools, LLM Development, Software Engineering, Automation